Bigtable: A Distributed Storage System for Structured Data

Abstract

Bigtable is a distributed storage system for managing structured data that is designed to scale to a very large size: petabytes of data across thousands of commodity servers. Many projects at Google store data in Bigtable, including web indexing, Google Earth, and Google Finance. These applications place very different demands on Bigtable, both in terms of data size (from URLs to web pages to satellite imagery) and latency requirements (from backend bulk processing to real-time data serving). Despite these varied demands, Bigtable has successfully provided a flexible, high-performance solution for all of these Google products. In this paper we describe the simple data model provided by Bigtable, which gives clients dynamic control over data layout and format, and we describe the design and implementation of Bigtable.

Introduction

- Bigtable has achieved several goals: wide applicability, scalability, high performance, and high availability.

- Bigtable does not support a full relational data model; instead, it provides clients with a simple data model that supports dynamic control over data layout and format, and allows clients to reason about the locality properties of the data represented in the underlying storage.

- Data is indexed using row and column names that can be arbitrary strings.

- Bigtable also treats data as uninterpreted strings, although clients often serialize various forms of structured and semi-structured data into these strings.

- Clients can control the locality of their data through careful choices in their schemas.

- Bigtable schema parameters let clients dynamically control whether to serve data out of memory or from disk.

Data Model

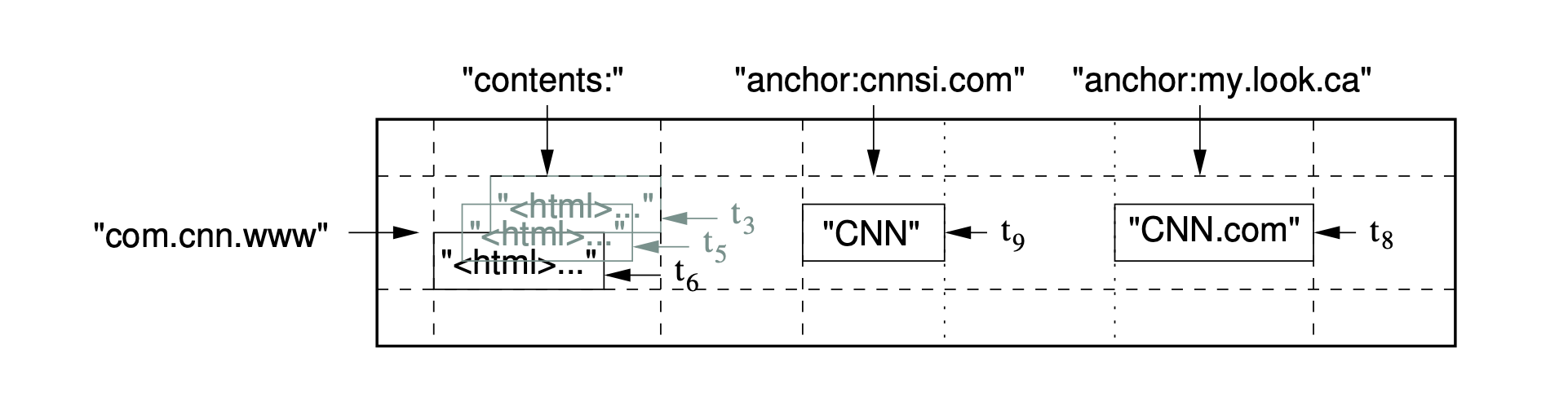

- A Bigtable is a sparse, distributed, persistent multi-dimensional sorted map. The map is indexed by a row key, column key, and a timestamp; each value in the map is an uninterpreted array of bytes.

(row:string, column:string, time:int64) → string

- Rows: Every read or write of data under a single row key is atomic (regardless of the number of different columns being read or written in the row), a design decision that makes it easier for clients to reason about the system’s behavior in the presence of concurrent updates to the same row. Bigtable maintains data in lexicographic order by row key. The row range for a table is dynamically partitioned. Each row range is called a tablet, which is the unit of distribution and load balancing. As a result, reads of short row ranges are efficient and typically require communication with only a small number of machines.

- Column Families: Column keys are grouped into sets called column families, which form the basic unit of access control. All data stored in a column family is usually of the same type (we compress data in the same column family together). The number of distinct column families in a table should be small (in the hundreds at most), and families shloud rarely change during operation. In contrast, a table may have an unbounded number of columns. Access control and both disk and memory accounting are performed at the column-family level.

- Timestamps: To make the management of versioned data less onerous, they support two per-column-family settings that tell Bigtable to garbage-collect cell versions automatically. The client can specify either that only the last n versions of a cell be kept, or that only new-enough versions be kept (e.g., only keep values that were written in the last seven days).

API

- The Bigtable API provides functions for creating and deleting tables and column families. It also provides functions for changing cluster, table, and column family metadata, such as access control rights.

- Client applications can write or delete values in Bigtable, look up values from individual rows, or iterate over a subset of the data in a table.

- Bigtable supports single-row transactions, which can be used to perform atomic read-modify-write sequences on data stored under a single row key.

- Bigtable allows cells to be used as integer counters.

- Bigtable supports the execution of client-supplied scripts in the address spaces of the servers. The scripts are written in a language developed at Google for processing data called Sawzall.

- A set of wrappers allow a Bigtable to be used both as an input source and as an output target for MapReduce jobs.

Building Blocks

- Bigtable uses the distributed Google File System (GFS) to store log and data files.

- Bigtable depends on a cluster management system for scheduling jobs, managing resources on shared machines, dealing with machine failures, and monitoring machine status.

- The Google SSTable file format is used internally to store Bigtable data. An SSTable provides a persistent, ordered immutable map from keys to values, where both keys and values are arbitrary byte strings.

- A block index (stored at the end of the SSTable) is used to locate blocks; the index is loaded into memory when the SSTable is opened.

- Bigtable relies on a highly-available and persistent distributed lock service called Chubby. Chubby uses the Paxos algorithm to keep its replicas consistent in the face of failure.

- Each Chubby client maintains a session with a Chubby service. A client’s session expires if it is unable to renew its session lease within the lease expiration time. When a client’s session expires, it loses any locks and open handles. Chubby clients can also register callbacks on Chubby files and directories for notification of changes or session expiration.

- Bigtable uses Chubby for a variety of tasks: to ensure that there is at most one active master at any time; to store the bootstrap location of Bigtable data; to discover tablet servers and finalize tablet server deaths; to store Bigtable schema information (the column family information for each table); and to store access control lists.

Implementation

- The Bigtable implementation has three major components: a library that is linked into every client, one master server, and many tablet servers.

- The master is responsible for assigning tablets to tablet servers, detecting the addition and expiration of tablet servers, balancing tablet-server load, and garbage collection of files in GFS. In addition, it handles schema changes such as table and column family creations.

- The tablet server handles read and write requests to the tablets that it has loaded, and also splits tablets that have grown too large.

- A Bigtable cluster stores a number of tables. Each table consists of a set of tablets, and each tablet contains all data associated with a row range. Initially, each table consists of just one tablet. As a table grows, it is automatically split into multiple tablets, each approximately 100-200 MB in size by default.

- A three-level hierarchy analogous to that of a B+tree stores tablet location information.

- Bigtable uses Chubby to keep track of tablet servers. When a tablet server starts, it creates, and acquires an exclusive lock on, a uniquely-named file in a specific Chubby directory.

- The master executes the following steps at startup.

- The master grabs a unique master lock in Chubby, which prevents concurrent master instantiations.

- The master scans the servers directory in Chubby to find the live servers.

- The master communicates with every live tablet server to discover what tablets are already assigned to each server.

- The master scans the

METADATAtable to learn the set of tablets. Whenever this scan encounters a tablet that is not already assigned, the master adds the tablet to the set of unassigned tablets, which makes the tablet eligible for tablet assignment.

- When the memtable size reaches a threshold, the memtable is frozen, a new memtable is created, and the frozen memtable is converted to an SSTable and written to GFS.

Refinements

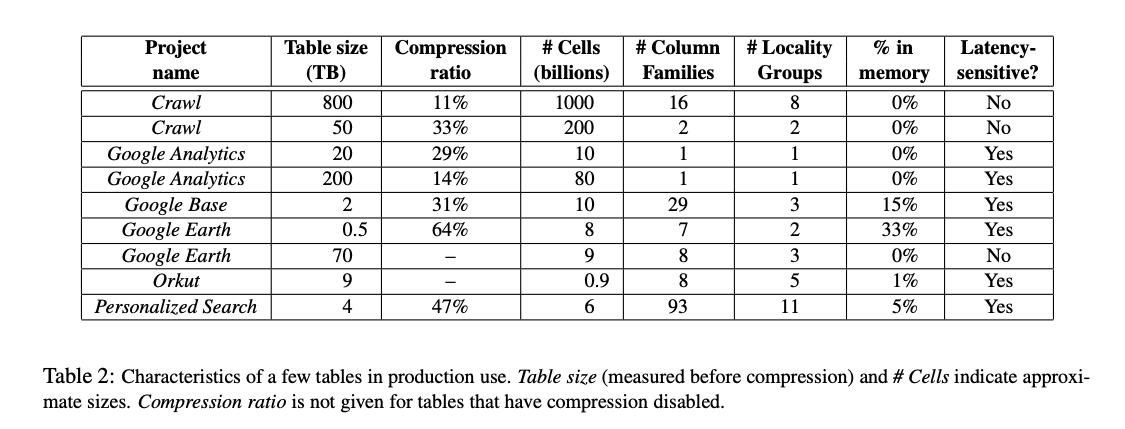

- Locality groups: Segregating column families that are not typically accessed together into separate locality groups enables more efficient reads.

- Compression: Clients can control whether or not the SSTables for a locality group are compressed, and if so, which compression format is used. Many clients use a two-pass custom compression scheme. The first pass uses Bentley and McIlroy’s scheme, which compresses long common strings across a large window. The second pass uses a fast compression algorithm that looks for repetitions in a small 16 KB window of the data. Both compression passes are very fast—they encode at 100–200 MB/s, and decode at 400–1000 MB/s on modern machines.

- Caching for read performance: The Scan Cache is a higher-level cache that caches the key-value pairs returned by the SSTable interface to the tablet server code. The Block Cache is a lower-level cache that caches SSTables blocks that were read from GFS.

- Bloom filters: A Bloom filter allows us to ask whether an SSTable might contain any data for a specified row/column pair. For certain applications, a small amount of tablet server memory used for storing Bloom filters drastically reduces the number of disk seeks required for read operations.

- Commit-log implementation: Using one log provides significant performance benefits during normal operation, but it complicates recovery.

- Speeding up tablet recovery: Before it actually unloads the tablet, the tablet server does another (usually very fast) minor compaction to eliminate any remaining uncompacted state in the tablet server’s log that arrived while the first minor compaction was being performed.

- Exploiting immutability: The only mutable data structure that is accessed by both reads and writes is the memtable. To re- duce contention during reads of the memtable, we make each memtable row copy-on-write and allow reads and writes to proceed in parallel. The immutability of SSTables enables us to split tablets quickly. Instead of generating a new set of SSTables for each child tablet, we let the child tablets share the SSTables of the parent tablet.

Real Applications

As of August 2006, there are 388 non-test Bigtable clusters running in various Google machine clusters, with a combined total of about 24,500 tablet servers.

- Google Analytics: The raw click table ( ̃200 TB) maintains a row for each end-user session. The row name is a tuple containing the website’s name and the time at which the session was created. This schema ensures that sessions that visit the same web site are contiguous, and that they are sorted chronologically. This table compresses to 14% of its original size. The summary table ( ̃20 TB) contains various predefined summaries for each website. This table is generated from the raw click table by periodically scheduled MapReduce jobs.

- Google Earth: Each row in the imagery table corresponds to a single geographic segment. Rows are named to ensure that adjacent geographic segments are stored near each other. The preprocessing pipeline relies heavily on MapReduce over Bigtable to transform data. The overall system processes over 1 MB/sec of data per tablet server during some of these MapReduce jobs.

- Personalized Search: Personalized Search generates user profiles using a MapReduce over Bigtable. These user profiles are used to personalize live search results.

Lessons

- Large distributed systems are vulnerable to many types of failures, not just the standard network partitions and fail-stop failures assumed in many distributed protocols.

- It is important to delay adding new features until it is clear how the new features will be used.

- The most important lesson we learned is the value of simple designs. Given both the size of the system (about 100,000 lines of non-test code), as well as the fact that code evolves over time in unexpected ways, we have found that code and design clarity are of immense help in code maintenance and debugging.

Over the next few Saturdays, I'll be going through some of the foundational papers in Computer Science, and publishing my notes here. This is #6 in this series.