Immutability Changes Everything

Abstract

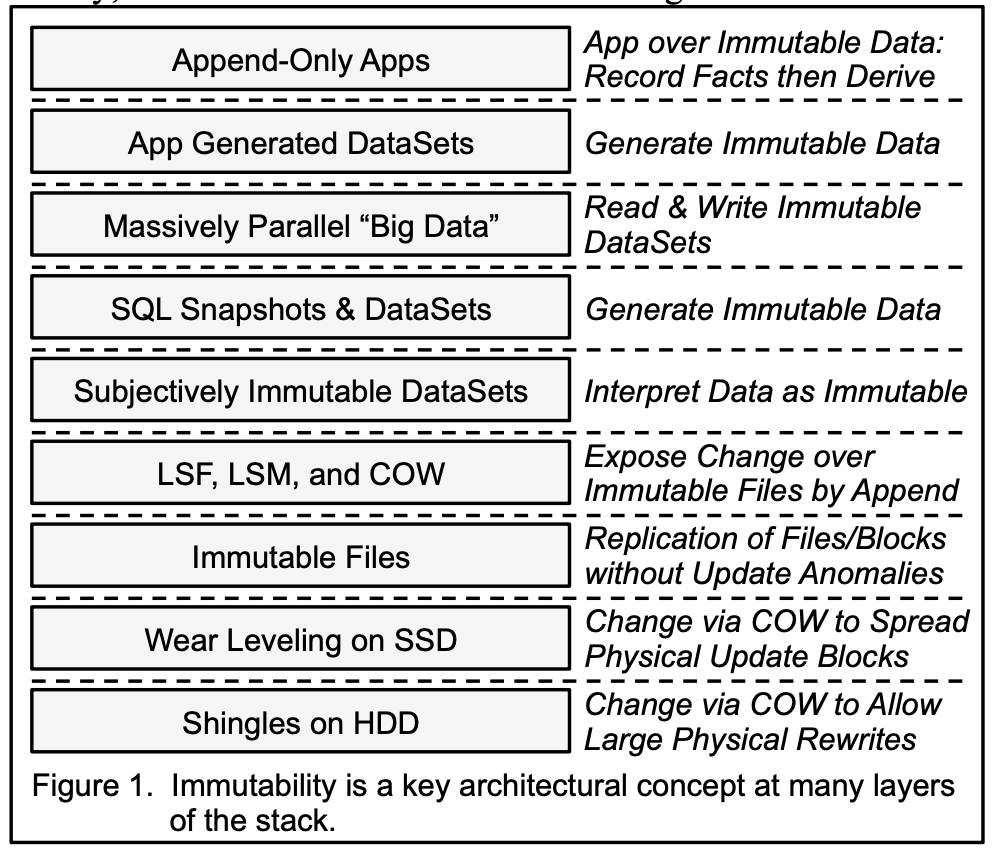

There is an inexorable trend towards storing and sending immutable data. We need immutability to coordinate at a distance and we can afford immutability, as storage gets cheaper. This paper is simply an amuse-bouche on the repeated patterns of computing that leverage immutability. Climbing up and down the compute stack really does yield a sense of déjà vu all over again.

Introduction

This is a fantastic, thought-provoking paper that goes deep into how the concept of immutability is not only something that we can now afford, but also makes distributed systems (and big data) possible in the first place. The paper explores how apps use immutability in their ongoing work, how apps generate immutable DataSets for later offline analysis, how SQL can expose and process immutable snapshots, how massively parallel “Big Data” work relies on immutable DataSets. In addition, updatability is layered atop the creation of new immutable files via techniques like LSF (Log Structure File systems), COW (Copy on Write), and LSM (Log Structured Merge trees). Finally, hardware folks have joined the party by leveraging these tricks in SSD and HDD. As the author says, it's turtles all the way down!

Accountants Don't Use Erasers

- Many kinds of computing are “Append-Only”. Observations are recorded forever (or for a long time). Derived results are calculated on demand (or periodically pre-calculated). This is similar to a DBMS — the database is a cache of a subset of the log.

- Some entries describe observed facts. Some entries describe derived facts.

- Single master computing means somehow we order the changes. The order can come from a centralized master or some Paxos-like distributed protocol providing serial ordering. Somehow, we semantically apply the changes one at a time.

- Before computers, workflow was frequently captured in paper forms with multiple parts on the form and multiple pages — back in the day, distributed computing was append-only!

Data on the Outside vs. Data on the Inside

- Data on the inside refers to stuff kept and managed by a classic relational database systems and its surrounding application code. Data on the inside lives in a transactional world with changes applied in a serializable fashion.

- Data on the outside is prepared as messages, files, documents, and/or web pages. Data on the outside is immutable, unlocked, has identity and could be versioned.

Referencing Immutable Data

- Immutable DataSets may be referenced by a relational DBMS. The metadata is visible to the DBMS. The data can be accessed for read, even though it may not be updated. Because the DataSet is immutable, there’s no need for locking and no worries about controlling updates.

- When we have snapshots or some form of isolation, database data becomes semantically immutable for the duration of the calculation.

- Also, the JOINs and other relational operators must necessarily combine the contents of the DataSet as interpreted as a set of relational tables. This sidesteps the notion of identity within the DataSet and focuses exclusively on the tables as interpreted as a set of values held within rows and columns.

Immutability Is in the Eye of the Beholder

- What’s important about a DataSet is that it appears to be unchanging from the standpoint of the reader.

- DataSets are semantically immutable but may be physically changed. You can add an index or two. It’s OK to denormalize tables to optimize for read access. DataSets may be partitioned and the pieces placed close to their readers. A column-oriented representation of a DataSet may make a lot of sense, too!

- Massively parallel computations are based on immutable inputs and functional calculations. Immutability is the backbone of "Big Data".

- When creating an immutable DataSet, the semantics of the data may not be changed. All we can do is describe the contents the way they are at the time the DataSet is created.

- Normalization’s goal is to eliminate update anomalies. Normalization is not necessary in an immutable DataSet.

Versions are Immutable Too!

- A linear version history is sometimes referred to as being strongly consistent. One version replaces another. There’s one parent and one child. Alternatively, you may have a DAG or directed acyclic graph of version history.

- Strongly consistent (ACID) transactions appear as if they run in a serial order. This is sometimes called serializability. Alternatively, you can capture the new version as changes to the previous version. You can build a key-value store this way. You can build a relational database atop a key-value store. Records are deleted by adding tombstones.

- If a timestamp is added to each new version, it is possible to show the state of the DB as-of a point in time. This allows the user to navigate the state of the database to any old version. Ongoing work can see a stable snapshot of a version of the database.

- With an LSM (Log Structured Merge tree), changes to the key-value store are accomplished by writing new versions of the affected records. LSM presents a facade of change atop immutable files.

- High-performance copy-on-write happens with logging and classic DBMS performance techniques.

Keeping the Stone Tablets Safe

- An early example of reifying change through immutability is Log Structured File Systems. In this wonderful invention, file system writes are always appended to the end of a circular buffer. Occasionally, enough meta-data to reconstruct the file system is added to the circular buffer. Old stuff must be copied forward so it is not overwritten.

- In GFS, HDFS, etc., each file is immutable and (typically) single writer. The file is created and one process can append to it. The file lives for a while and is eventually deleted. Multi-writers are hard and GFS had some challenges with this.

- When reading and updating within a consistent hashing key-value store, the read occasionally yields an older version of the value. To cope with this, the application must be designed to make the data eventually consistent, which is a burden and makes application development more difficult. When storing immutable data within a consistent hash ring, you cannot get stale versions of the data. Each block stored has the only version it will ever have!

- In a distributed cluster, you can know where you are writing or you can know when the write will complete but not both.

- Immutability allows decentralized recovery of Data Node failures with more predictable SLAs.

Hardware Changes towards Unchanging

- SSDs and Wear Leveling: The flash chip within most SSDs is broken into physical blocks, each of which has an finite number of times it may be written before it begins to wear our and give increasingly unreliable results. Consequently, chip designers have a feature known as wear leveling to mitigate this aspect of flash. Each new write (or update to a new block) is written to a different physical block in a circular fashion, evening out the writes so each physical block is written about as often as the others.

- Hard Disk Shingles: Current designs have a much larger write track than read track. Writes overlap the previous ones in a fashion evocative of laying shingles on a roof. Hence the name “Shingled Disk Systems”. To overcome this, the hardware disk controllers implement log-structured file systems within the disk controller.

Immutability May Have Some Dark Sides

- Denormalization consumes storage as a data item is copied multiple times in a DataSet.

- Data may be copied many times when we use copy on write. This is known as write amplification. In many cases, there is a relationship between the amount of write amplification and the difficulty involved in reading the data being managed.

Conclusion

Immutability does change everything!

Over the next few Saturdays, I'll be going through some of the foundational papers in Computer Science, and publishing my notes here. This is #12 in this series.