Spanner: Google’s Globally-Distributed Database

Abstract

Spanner is Google’s scalable, multi-version, globally-distributed, and synchronously-replicated database. It is the first system to distribute data at global scale and support externally-consistent distributed transactions. This paper describes how Spanner is structured, its feature set, the rationale underlying various design decisions, and a novel time API that exposes clock uncertainty. This API and its implementation are critical to supporting external consistency and a variety of powerful features: non-blocking reads in the past, lock-free read-only transactions, and atomic schema changes, across all of Spanner.

Introduction

- At the highest level of abstraction, Spanner is a database that shards data across many sets of Paxos state machines in data centers spread all over the world.

- Replication is used for global availability and geographic locality; clients automatically failover between replicas. Spanner automatically reshards data across machines as the amount of data or the number of servers changes, and it automatically migrates data across machines (even across datacenters) to balance load and in response to failures.

- Spanner is designed to scale up to millions of machines across hundreds of datacenters and trillions of database rows.

- Initial customer was F1, a rewrite of Google’s advertising backend.

- Spanner’s main focus is managing cross-datacenter replicated data, but they have also spent a great deal of time in designing and implementing important database features on top of our distributed-systems infrastructure. Even though many projects happily use Bigtable, they have also consistently received complaints from users that Bigtable can be difficult to use for some kinds of applications: those that have complex, evolving schemas, or those that want strong consistency in the presence of wide-area replication.

- As a consequence, Spanner has evolved from a Bigtable-like versioned key-value store into a temporal multi-version database.

- Data is stored in schematized semi-relational tables; data is versioned, and each version is automatically timestamped with its commit time; old versions of data are subject to configurable garbage-collection policies; and applications can read data at old timestamps.

- Spanner supports general-purpose transactions, and provides a SQL-based query language.

Features

As a globally-distributed database, Spanner provides several interesting features:

- First, the replication configurations for data can be dynamically controlled at a fine grain by applications. Applications can specify constraints to control which datacenters contain which data, how far data is from its users (to control read latency), how far replicas are from each other (to control write latency), and how many replicas are maintained (to control durability, availability, and read performance).

- Second, Spanner has two features that are difficult to implement in a distributed database: it provides externally consistent reads and writes, and globally-consistent reads across the database at a timestamp.

- In addition, the serialization order satisfies external consistency (or equivalently, linearizability): if a transaction T1 commits before another transaction T2 starts, then T1’s commit timestamp is smaller than T2’s. Spanner is the first system to provide such guarantees at global scale.

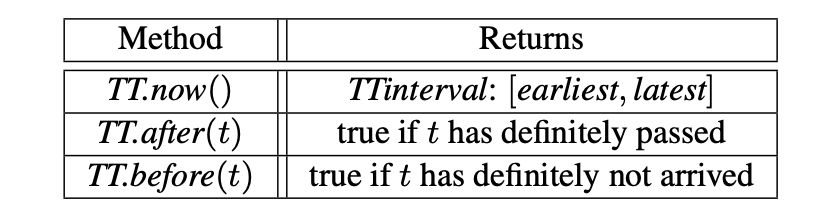

- The key enabler of these properties is a new TrueTime API and its implementation. This implementation keeps uncertainty small (generally less than 10ms) by using multiple modern clock references (GPS and atomic clocks).

Implementation

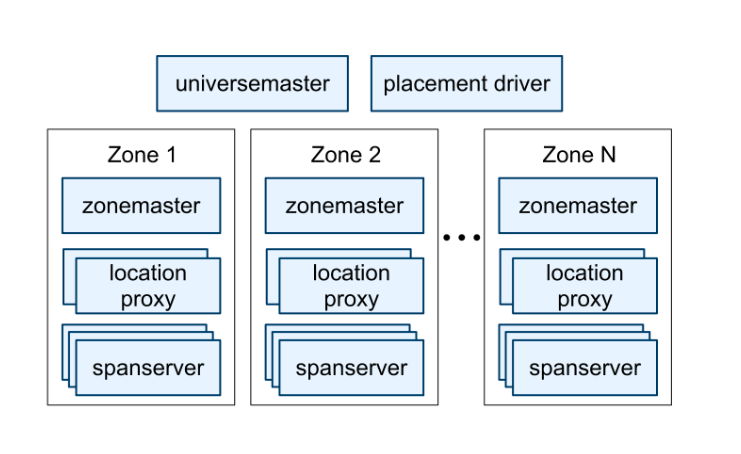

- A Spanner deployment is called a universe. Zones are the unit of administrative deployment. Zones are also the unit of physical isolation: there may be one or more zones in a datacenter, for example, if different applications’ data must be partitioned across different sets of servers in the same datacenter.

- A zone has one zonemaster and between one hundred and several thousand spanservers. The former assigns data to spanservers; the latter serve data to clients. The per-zone location proxies are used by clients to locate the spanservers assigned to serve their data.

- The universe master is primarily a console that displays status information about all the zones for interactive debugging. The placement driver handles automated movement of data across zones on the timescale of minutes. The placement driver periodically communicates with the spanservers to find data that needs to be moved, either to meet updated replication constraints or to balance load.

Spanserver Software Stack

- At the bottom, each spanserver is responsible for between 100 and 1000 instances of a data structure called a tablet. A tablet is similar to Bigtable’s tablet abstraction.

- Unlike Bigtable, Spanner assigns timestamps to data, which is an important way in which Spanner is more like a multi-version database than a key-value store.

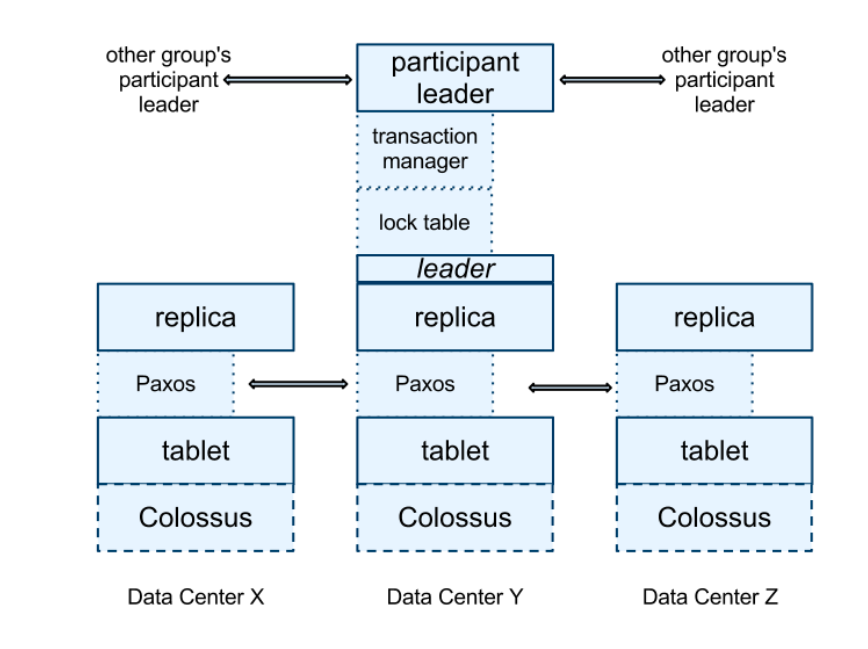

- A tablet’s state is stored in set of B-tree-like files and a write-ahead log, all on a distributed file system called Colossus (the successor to the Google File System).

- The Paxos state machines are used to implement a consistently replicated bag of mappings. The key-value mapping state of each replica is stored in its corresponding tablet. Writes must initiate the Paxos protocol at the leader; reads access state directly from the underlying tablet at any replica that is sufficiently up-to-date. The set of replicas is collectively a Paxos group.

- At every replica that is a leader, each spanserver implements a lock table to implement concurrency control. The lock table contains the state for two-phase locking: it maps ranges of keys to lock states.

- At every replica that is a leader, each spanserver also implements a transaction manager to support distributed transactions. The transaction manager is used to implement a participant leader; the other replicas in the group will be referred to as participant slaves.

Directories and Placement

- A directory is the unit of data placement. All data in a directory has the same replication configuration. When data is moved between Paxos groups, it is moved directory by directory.

- A directory is also the smallest unit whose geographic-replication properties (or placement, for short) can be specified by an application.

- Spanner will shard a directory into multiple fragments if it grows too large. Fragments may be served from different Paxos groups (and therefore different servers).

Data Model

- Spanner exposes the following set of data features to applications: a data model based on schematized semi-relational tables, a query language, and general-purpose transactions.

- The need to support schematized semi-relational tables and synchronous replication is supported by the popularity of Megastore.

- The lack of cross-row transactions in Bigtable led to frequent complaints; Percolator was in part built to address this failing.

- Authors believe it is better to have application programmers deal with performance problems due to overuse of transactions as bottlenecks arise, rather than always coding around the lack of transactions. Running two-phase commit over Paxos mitigates the availability problems.

- Spanner’s data model is not purely relational, in that rows must have names. More precisely, every table is required to have an ordered set of one or more primary-key columns. This requirement is where Spanner still looks like a key-value store: the primary keys form the name for a row, and each table defines a mapping from the primary-key columns to the non-primary-key columns.

True Time

- The time epoch is analogous to UNIX time with leap-second smearing.

- The underlying time references used by TrueTime are GPS and atomic clocks.

- TrueTime uses two forms of time reference because they have different failure modes:

- GPS reference-source vulnerabilities include antenna and receiver failures, local radio interference, correlated failures (e.g., design faults such as incorrect leap-second handling and spoofing), and GPS system outages.

- Atomic clocks can fail in ways uncorrelated to GPS and each other, and over long periods of time can drift significantly due to frequency error.

Concurrency Control

The Spanner implementation supports read-write transactions, read-only transactions (predeclared snapshot-isolation transactions), and snapshot reads. This section is a masterclass in managing distributed read/writes, and I definitely recommend you to check out the the full section in the paper.

Other Interesting Stuff

- Google machine statistics show that bad CPUs are 6 times more likely than bad clocks. That is, clock issues are extremely infrequent, relative to much more serious hardware problems. As a result, we believe that True-Time’s implementation is as trustworthy as any other piece of software upon which Spanner depends.

- F1 as the first client: Spanner started being experimentally evaluated under production workloads in early 2011, as part of a rewrite of Google’s advertising backend called F1. The uncompressed dataset is tens of terabytes, which is small compared to many NoSQL instances, but was large enough to cause difficulties with sharded MySQL. The F1 team chose to use Spanner for several reasons:

- First, Spanner removes the need to manually reshard.

- Second, Spanner provides synchronous replication and automatic failover.

- Third, F1 requires strong transactional semantics, which made using other NoSQL systems impractical.

Conclusions

To summarize, Spanner combines and extends on ideas from two research communities: from the database community, a familiar, easy-to-use, semi-relational interface, transactions, and an SQL-based query language; from the systems community, scalability, automatic sharding, fault tolerance, consistent replication, external consistency, and wide-area distribution.

Over the next few Saturdays, I'll be going through some of the foundational papers in Computer Science, and publishing my notes here. This is #10 in this series.